Everyone knows something about Genghis Khan. His story and empire is part of the basic history of the world we learn growing up. He came into power by uniting disparate tribal groups of Northeastern Asia. His Mongol invasions over the early 13th century AD resulted in the massacre of thousands of people and unification of a large portion of Eurasia. After his death, his many descendants continued his legacy and spread out across the Middle East and Eastern Europe. He was buried in an unknown location in Mongolia with no markings to commemorate him; this was his choice, and was a custom among his people. His story and life are known from writing and art, but what about the thousands of people he led? How did these people live and die? Most importantly, how did life change for the Mongolians as they evolved from small tribal communities to one of the greatest empires in history?

A new article by Fenner, Tumen and Khatanbaatar (2014) examines changes in diet of the Mongolian people during this period of change in the 13th century. Primarily, they focus on whether diet changed more at the elite level, as these individuals would have greater access to foreign items. As the Mongol Empire began, there is little written information available from themselves- however there are accounts of them from foreigners. By the early 13th century, there is written information from the elite of the Mongolian Empire, though it is limited. As pastoralists, it is expected that diet of both elite and commoners will be focused on meat and other animal by-products. Their own history describes the range of meats they ate, and accounts from others also notes a preference for meat and dairy over vegetables or grains. Some grains are described in texts, but it is unknown whether this represents rice or millet- and it was introduced into the diet later as the Mongols conquered agricultural territories.

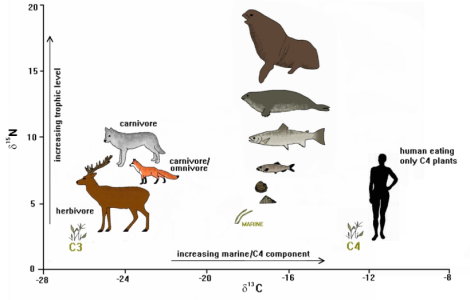

In order to investigate diet, Fenner, Tumen and Khatanbaatar (2014) use stable isotope analysis. Nitrogen isotope ratios (N15) are correlated with trophic levels, therefore plants have lower ratios than the herbivorous animals that eat them, which in turn are eaten by carnivorous animals who have an even higher ratio. The ratios can vary by the environment as increased aridity and salinity can cause the base level of plants to be higher, and therefore all other trophic levels are higher. Different plants can also vary, for example legumes are lower than cereals which are lower than fruits. Carbon isotope ratios vary by the type of plants consumed. The more marine life and C4 plants consumed, the higher the carbon ratio, whereas a lower ratio means more animal and C3 consumption. C4 plants are able to deal with harsher environments and include plants like maize and millet. Most other types of plants are C3.

Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope composition of several different organisms (http://chrono.qub.ac.uk/ adapted from Schulting, 1998, via Emma Veerstegh).

Three cemeteries from the Empire period were investigated for this analysis: Tavan Tolgoi (interpreted as associated with the ruling elite), Tsagaan chuluut (interpreted as incorporating lesser elites and perhaps commoners) and Ulaanzuukh (mainly commoners). Tavan Tolgoi was excavated in 2004 and 2005. Of the eight burials excavated, most had exotic luxury grave goods and animal remains with them. Six of the burials date to the late 13th century. Of special significance in this cemetery was the presence of two gold rings with falcons; these indicate close ties of these individuals to the lineage of Genghis Khan. Tsagaan chuluut was excavated from 2008-2010. Of the 163 graves with markers, only 14 were excavated. Each burial had a variety of grave goods, however they are primarily common items. Burials date to the mid-13th century. Ulaanzuukh was excavated in 2008-2010, and another 14 graves were excavated. Very few grave goods were excavated, indicating that they were common burials. We selected bones in visibly good condition from each site.

Samples were obtained from seven individuals from Tavan Tolgoi, eleven individuals from Tsagaan chuluut, and thirteen individuals from Ulaanzuukh. In addition to this, four horses and two goat/sheep were sampled from the Tavan Tolgoi burials. The burials from Tavan Tolgoi have significantly higher N15 values than either Tsagaan chuluut and Ulaanzuukh. Based on this, it would be assumed that the former is consuming more meat than the two latter sites, meaning that elites had more access to this type of food. However, they also compared the stable isotope ratios to other sites and analyses done in the broader region. From this, it appears that the isotopic differences may not be indicative of diet, but rather different environments which cause the nitrogen and carbon ratios to vary. They conclude that there were not substantial dietary differences despite the difference in grave goods. Fenner, Tumen and Khatanbaatar (2014) note that sample size for this was small, and future studies should investigate the environmental links further.

I think this conclusion is interesting given that the data initially pointed to elites eating more meat, and they questioned it. Often when we see stable isotope analyses there is a leap from ratio to diet- however there are many unknowns and variables we need to account for. Stay tuned for another stable isotope study this week!

**Photo was changed due to incorrect labeling, thanks to reader Lim TT for pointing this out!**

Works Cited

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Katy is an anthropology PhD student who specializes in mortuary archaeology and bioarchaeology at Michigan State University

0 comments:

Post a Comment