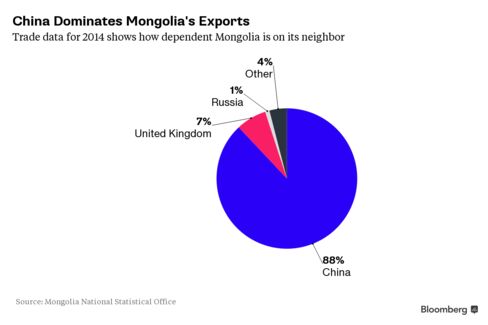

- With 88% of exports winding up in China, Mongolia badly hurt

- China's neighbor looking to sell power plants, postal service

While China’s slowing economy has singed stock markets around the world, no nation is more affected than neighboring Mongolia. Things have gotten so bad that the government in this mineral-rich nation is planning job and salary cuts for bureaucrats, and the sale of of shares in state-owned companies including the postal service.

Mongolia, sandwiched between China and Russia, is an early illustration of fallout from slower growth in the world’s second-biggest economy. “When China sneezes, we get a cold. That is how the situation is. It really affects us in a major way,” Dale Choi, founder and director of the research firm Independent Mongolian Metal & Mining Research, said in a phone interview.

That’s because about 88 percent of Mongolia’s exports -- mostly commodities including coal -- wound up in China in 2014 and falling revenue from these products is pushing Mongolia deeper into economic crisis. Earlier this month the country’s Finance Minister Bolor Bayarbaatar unveiled emergency austerity measures so the government can pay its bills.

The sliding commodity prices are exacerbating existing woes for Mongolia, which has had a sharp downturn in foreign direct investment because of the price decline as well as some disputes with foreign companies like Rio Tinto Plc.

If passed by parliament, the austerity measures would eliminate government jobs, cut salaries and merge agencies in an effort to reduce spending. Revenue-raising plansinclude selling off shares of power plants and the postal service, which are relics of a Soviet era and continue to bleed red ink -- something the government can no longer afford.

While austerity may not be encouraging for a government that faces a contested election in eight months, Prime Minister Saikhanbileg Chimed has few other options. His finance minister reported that the 2015 budget will face a shortfall of more than 4 percent, or $500 million, by the end of the year -- a considerable sum for a $12 billion economy.

Mongolia’s gross domestic product growth has fallen to the current pace of about 3 percent from more than 17 percent in 2011. In August, the sovereign’s Chinggis bond, issued in 2012, slid at the fastest pace in two years before recovering slightly. Its currency, the tugrik, has tumbled to record lows.

Commodity Collapse

China’s slowing demand has played no small part in Mongolia’s economic decline. In the first nine months of this year Mongolia exported $3 billion worth of products to China, down from $3.6 billion in the same period a year earlier, a fall of 17 percent.

Employees walk to work from the living quarters at the Oyu Tolgoi copper-gold mine. China’s slowing demand has played no small part in Mongolia’s economic decline. In the first nine months of this year Mongolia exported $3 billion worth of products to China, down from $3.6 billion in the same period a year earlier.

Photographer: Brent Lewin/Bloomberg

Revenues are down sharply for Mongolia’s commodities exports: a 32 percent drop for coal, 41 percent for oil and 48 percent for iron ore. Only the value of copper shipments has shown an increase, up 1.9 percent in September from the previous year, largely because of a ramp-up in production at the new Oyu Tolgoi copper mine.

“Now, everything will depend on how competitive we are,” said Choi, who is based in Ulaanbaatar and has been analyzing Mongolia’s commodities market for six years. “If we do nothing, the trend will be a continued decline. The prices are going down but China will continue to buy, so we just need to deliver at lower prices and still make money, which means improving infrastructure.”

Mongolia’s economy could worsen if the export picture with China doesn’t improve soon. A recent report by the Asian Development Bank forecast growth for the whole of 2015 slowing to 2.3 percent, before a recovery to 3 percent in 2016.

Soviet Period

Mongolia’s big push in commodities is still a relatively recent phenomenon. Soviet geologists began mapping out the country from the 1950s, paving the way for a handful of coal mines and the Erdenet copper mine, which shipped all its product to the USSR.

An illuminated statue of Damdid Sukhbaatar, right, stands on Chinggis Khaan Square.

Photographer: Brent Lewin/Bloomberg

When private enterprise arrived in the 1990s, Mongolian entrepreneurs started mining outfits and were joined by a handful of Chinese and Western companies. The most successful was undoubtedly Ivanhoe Mines (now Turquoise Hill Resources Ltd.) which explored and developed the giant Oyu Tolgoi deposit.

Cashmere, Tourism

Mongolia’s reliance on China’s commodity appetite was more opportunistic than planned. In fact, successive governments have tried to diversify the export economy away from mining. The government has backed projects to develop the dairy and meat industry, leather, cashmere, tourism and even gambling as ways to overcome its reliance on mining exports. Still, mining today accounts for 79 percent of exports.

And Mongolia has not always leaned so heavily on China. For most of the 20th century the nation was a client of Moscow and the bulk of its raw materials were shipped north to the USSR. A peaceful transition to democracy 25 years ago opened up new markets to Mongolia. A “third neighbor policy” was developed so that it could seek economic ties with the U.S., Japan, Germany and other Western countries.

But China, which shares a 2,906-mile border with Mongolia’s southern frontier, quickly became the number one trading partner.

Mongolia’s cashmere producers were the first to make inroads in China, followed quickly by the mining companies. Today cashmere only makes up about 6 percent of the exports Mongolia sends to China. The rest are minerals.

Mongolia , though, doesn’t blame all of its economic problems on China. The government is quick to point out that misguided policies have caused self-inflected wounds. The most drastic was the 2012 Strategic Entities Foreign Investment Law (SEFIL), which put an immediate chill on foreign investment in Mongolia.

FDI Discouraged

SEFIL’s purpose was to impose more government oversight of the sale of Mongolian assets to foreign entities. It was sparked after the Aluminum Corp. of China Ltd. made a bid to buy Mongolian coal miner SouthGobi Resources Ltd.

While the government successfully prevented the sale, the law caused overall foreign direct investment in the country to plunge more than 50 percent the next year.

John Johnson, chief executive of CRU China, a Beijing-based market analysis firm with a focus on commodities, said China’s slowdown has given Mongolia a lesson that the country should try to regain some foreign investment.

“The reality is hitting home in Mongolia that they have to change their view a little bit and they have to be a bit less hostile given the downturn in the commodity cycle,” Johnson said. But, he said, the potential to develop is still there: “China is still a huge market and Mongolia just needs to capture a small slice of that market.”

Source:Bloomberg

0 comments:

Post a Comment